Fastelavn buns are something most Scandinavian people feel a certain familiarity with. Fewer know what Fastelavn actually marks. Fewer still know what Ash Wednesday is. And for many Norwegians, Lent itself has become an unfamiliar word – either reduced to a form of dieting, or dismissed as a relic from a more austere age.

But Lent is no mere curiosity. It is one of Christianity’s oldest and most thoroughly biblical practices.

The Christian fast begins on Ash Wednesday and lasts until Easter Day: forty days (excluding the Sundays) in imitation of the time Jesus spent in the wilderness before entering Jerusalem to be arrested, crucified and to die for us.

Document asked Ole Martin Stamnestrø, Catholic parish priest in Drammen, to help us recover an understanding of the Lenten season – of what these Norwegian observance days truly signify, and how they lead up to the most important feast in the Church’s year: Easter.

For although the fasting regulations are less stringent than they once were, the purpose remains unchanged. Pater Ole Martin explains:

“Fasting is a biblical practice. For example, Jesus says to his disciples: ‘When you fast, do not look sombre like the hypocrites.’ (Mt. 6.16). The very word ‘fast’ derives from the Old Norse ‘fastr’, which means to hold fast. During Lent, we are therefore challenged to strip away all that distracts, all inessentials, and to hold fast to what is central – our Saviour Jesus Christ.”

Like all our other Christian feasts, it is not primarily about food – or the absence of it. It is about direction.

Pussy willows and Fastelavn twigs. Oslo, 2019. (Photo: Gorm Kallestad / NTB)

Fastelavn and Shrove Tuesday

Fastelavn is still observed in Norwegian homes and holiday cabins. Branches of pussy willow are brought indoors, birch twigs are adorned with brightly coloured feathers, and cream-filled buns are baked. Is it merely a touch of springtime high spirits and a fundraising effort for the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association? By no means. It marks the close of what, in the Church’s year, is known as the pre-Lenten season, which begins as early as seventy days before Easter.

Pater Ole Martin speaks with the authority of master’s and doctoral degrees in church and liturgical history:

“Fastelavn comprises the final days of the so-called pre-Lenten season. The pre-Lenten season begins with ‘Septuagesima Sunday’, the Sunday that falls 70 days before Easter Day. After ‘Septuagesima Sunday’ comes ‘Sexagesima Sunday’, and then follows ‘Quinquagesima Sunday’, which we also call ‘Fastelavn Sunday’, that is, the last Sunday before Ash Wednesday.”

So much for the chronology. In practical terms, the pre-Lenten season serves a straightforward and homely purpose, and the three final days before Lent still bear names familiar to most: Fastelavn Sunday, Blue Monday and Shrove Tuesday.

“On this Sunday and the two following days – Blue Monday and Shrove Tuesday – it is permissible to eat up the kind of food that we intend to abstain from during Lent,” says the parish priest.

It is therefore hardly surprising that these days have taken on a festive air. The carnival in Rio takes place at this time and is known throughout the world; so too the celebrations of Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Mardi Gras is French for “Fat Tuesday”, that is, Shrove Tuesday. A royal crown, often in the form of a cake (Galette des Rois – King cake), is a central symbol. Why? Because the crown refers to the Three Wise Men who visited the Christ Child. The tradition begins with Epiphany (Twelfth Night) on 6 January and lasts until Mardi Gras. In Denmark, all these elements are gathered together under Fastelavn: carnival, crowns, buns and fizzy drinks. It is, after all, the final opportunity to indulge before Lent begins. Yet Shrove Tuesday is not an observance day in the theological sense.

“Shrove Tuesday is not a feast day in the Church’s liturgical calendar. It is simply the last day on which one may, with a clear conscience, indulge a little before Lent itself begins,” explains Pater Ole Martin.

It is perhaps characteristic of our age that we have kept Shrove Tuesday – and forgotten Lent.

Fastelavn buns in the Norwegian style. (Photo: Colourbox)

Ash Wednesday – put your finger in the soil

Lent begins with ash. Not with inspiration, not with self-improvement – but with dust.

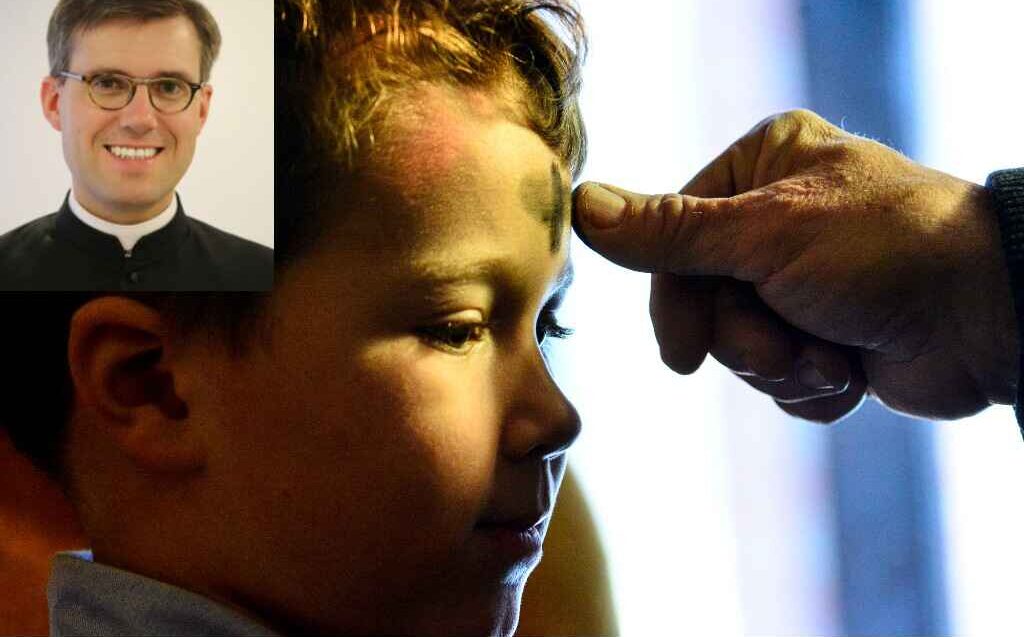

“Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent,” says Pater Ole Martin. “The Church then gives us a particular sacramental, namely the custom whereby the faithful come forward to receive a cross of ash either upon the head or on the forehead, while the priest says the words, ‘Remember, man, that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return.’”

The words resemble those spoken at a funeral: “Earth thou art, to earth shalt thou return, and from the earth shalt thou rise again.” Or, as it is more commonly rendered in English, “earth to earth, dust to dust.” They are not intended as morbidity, but as truth. To remember that we shall all die places life in its proper perspective. The Latin expression memento mori derives from ancient Roman tradition and holds a central place in Christian thought.

“It is sensible to begin Lent with a reality check,” Pater Ole Martin confirms. “We have not created ourselves. Life is a gift from God. In Genesis we hear how God formed man from ‘the dust of the ground’ (Gen. 2.7). God then breathes life into the dust. It is God who gives us life – and everything else. Ash Wednesday reminds us of the proper relationship between ourselves and God. All that we are and have comes from Him.”

In a culture that prizes self-creation and self-realisation, such a reminder may seem both unfamiliar – and liberating. The Protestant Church of Norway never entirely ceased to observe Ash Wednesday and Lent, although the traditions have been considerably weakened over time. In recent years, however, there has been renewed interest in Lent, and in 2024 the General Synod (Kirkemøtet) adopted a distinct liturgical order for Ash Wednesday, in which the imposition of ashes on the forehead or hand forms a central element.

How does one fast?

Historically, Lent was strict. The Crusaders’ observance was perhaps among the most rigorous: forty days without meat, dairy produce or eggs. Only fish, seafood and vegetables – together with prayer and penance.

Today, the minimum requirements are modest.

“The Church is a gracious Mother,” the parish priest assures us. “She sets very low minimum requirements with regard to fasting. There are, in fact, only two actual fast days remaining: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. On those days one may eat one normal meal and two smaller meals which together must not exceed the main meal.”

There is also abstinence from meat on certain days. Beyond these minimum requirements, however, lies an invitation to the faithful to relinquish something more – screen time, alcohol, chocolate or other comforts. Pater Ole Martin emphasises that the purpose is not self-mortification, but prioritisation:

“One clears space, as mentioned, for what is essential – for God – and therefore one must also remove time-consuming distractions, so as to have more time for prayer and spiritual reading. One’s time and energy should likewise be used to give alms and practise other good works.”

Discipline, humility and the modern person

Words such as discipline and renunciation jar in a culture that equates freedom with the absence of constraint. Yet the priest makes an interesting observation:

“We live in a time when many people, especially young men, are rediscovering ‘discipline’ as a good in itself. All athletes know that if one wishes to attain a goal, one must exercise a certain degree of self-discipline. In Lent, the goal one seeks to attain is a spiritual one, reached in part through bodily discipline.”

Humility, according to Pater Ole Martin, is not self-abasement but realism.

“Humility in Latin is humilitas, from the word humus, ‘earth’. We are thus brought back to the question of our origin. When we become conscious of this – of where we come from and of our dependence upon God – we become humble. Or ‘earthbound’. And that word carries a positive resonance in Norwegian.”

To know that one is dust – and loved – is not degrading. It is clarifying.

TV host Ainsley Earhardt (centre) together with Mark Wahlberg and Jonathan Roumie, with crosses of ash on their foreheads during a visit to “Fox & Friends”. Ash Wednesday, 2024. (Photo: Charles Sykes/Invision/AP)

Easter morning dispels sorrow (*)

Lent can, of course, become a performance. That danger is frequently noted, and the parish priest concurs.

“Yes, it is a real danger. Jesus warns us against it (cf. Mt. 6.16f). Most of us are confronted with our own weakness during Lent; we do not manage to give God as much as we had resolved. That discovery is an antidote to self-righteousness.”

When one falters during Lent, one learns something about oneself. Not how capable one is – but how dependent one truly is.

The good news is that Lent is not an end in itself. It points beyond itself.

“Easter is the greatest and most important feast of the Church’s year. We know that the second most important feast – Christmas – has its season of preparation in Advent. It follows, therefore, that Easter must have an even longer and more demanding preparation.”

In earlier times, the period from Maundy Thursday through the Easter weekend was observed as quiet days in Norway. The media offered little by way of entertainment, and shops remained closed. The solemnity of the feast marked those days more deeply than it does today. Yet Lent does not conclude in darkness. After Holy Saturday the fast is broken, and Easter Day opens into light and life.

“Lent reminds us that penance is an essential element of the Christian faith. We grieve over our sins and ask God for forgiveness. On Good Friday we see what that forgiveness costs. Sorrow for our sins is a prerequisite for sharing in the joy of the Resurrection. On Easter Day Lent is forgotten, and the joy of the Resurrection eclipses everything. We have begun the new life in Christ.”

Perhaps this is precisely what our age lacks: preparation before the celebration of Easter. Serious reflection before rejoicing. An exercise in relinquishing – so that one may truly receive. Lent is not an imposition. It is an invitation.

The question is not whether we can manage without chocolate for forty days. The question is whether we dare to hold fast to what truly matters.

(*) “Easter Morning dispels Sorrow” (“Påskemorgen slukker sorgen” ) is widely regarded as one of the most beautiful and beloved hymns in the Scandinavian Easter tradition. The text was written in 1852 by the Norwegian poet (and Nobel price laureate) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, and it has since become an integral part of Easter morning services across Norway and Denmark.

The hymn expresses the central paradox of Easter: that sorrow, darkness and death are overcome by the light of the Resurrection. Its language is both poetic and theologically rich, moving from the grief of Good Friday to the triumphant joy of Easter Day. For many Scandinavians, it is almost inseparable from the sound of church bells on Easter morning.

One of the most celebrated interpretations is by the renowned Norwegian Wagnerian soprano Kirsten Flagstad. Best known internationally for her performances at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and for her interpretations of Wagner’s great heroines, Flagstad also recorded sacred music, including this hymn. Her rendition lends the text a solemn grandeur and emotional depth that have made it particularly cherished in Norway.