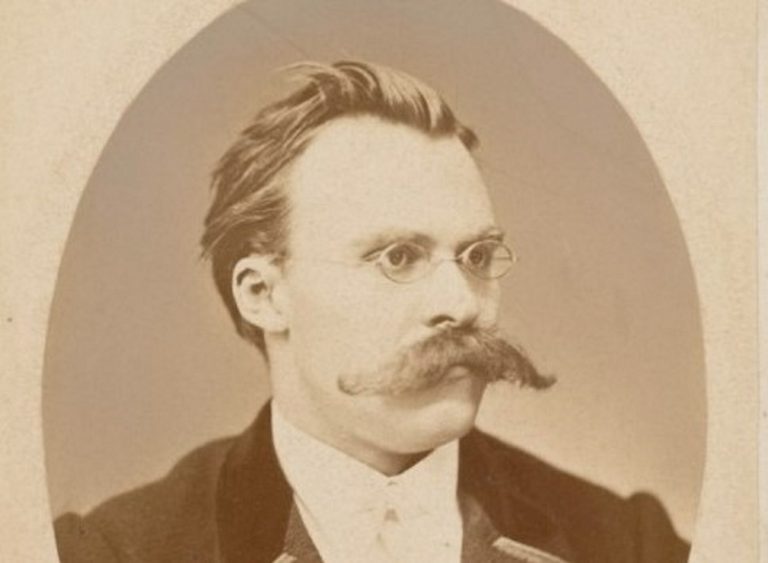

In Nietzsche’s “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”, Zarathustra, after ten years of solitary contemplation, finally descends from the mountain to enlighten the common people.

Zarathustra – who loves mankind – is looking forward to telling the truth, that God is dead and that man must recreate himself as “Übermensch”. He has no doubts about his persuasive arguments and launches into his monologue pretty much as soon as he arrives.

But the villagers think Zarathustra is the tightrope walker they’ve been waiting for and aren’t interested in his message. Eventually, Zarathustra realises that he is not getting through, and in desperation he attempts to introduce a hideous form of man – “the last man” (der letzte Mensch), an antithesis to the Übermensch. The descriptions are intended to be so repulsive that the villagers realise how important it is to embrace reality: God is dead, we must become Übermenschen to find meaning:

“But I will speak to them of the most despicable of all despicable things: but that is the last man. (…) Woe! The time will come when man will no longer give birth to a star. Woe! The most despicable time will come when man no longer can despise himself.”

“The last people” live in an aura of emptiness and false happiness. Everything is superficial, creativity is dead, there is no ambition, no will. </A full stomach and passive entertainment are sufficient. It’s a false sense of happiness, a self-deception – a betrayal of human potential. Not only God – but also Übermenschen – must die in such a world.

“What is love? What is creation? What is a star? So asks the last man and blinks.”

Of course, it all ends with the people in the marketplace ridiculing Zarathustra and shouting “let us be the last men!” No one is tempted by the far more demanding path of facing reality, then embracing the meaninglessness of existence, and choosing life fully as Übermensch.

“We’ve found happiness!” say the last people and wink!”

Nietszche writes about false pleasure, empty “happiness”. It’s not hard to recognise tendencies towards this in our time: Facebook, selfies, reality TV.

I would like to write a few words in the same spirit, but with the opposite sign: about false suffering, false emotions and false compassion, which we see many signs of in today’s postmodern reality. I choose to call this phenomenon sentimentality.

Sentimentality is emotions as accessories – something we decorate our self-image with. You could also describe sentimentality as a performance of compassion – we show others how “good” and “empathetic” we are.

<Moreover, sentimentality is a collective act in which we show how deeply we feel the suffering alongside others (praise train) – without needing to understand the background, causes and certainly not how to prevent what causes suffering, pain and grief from happening again – and again.

The sentimentalist shields himself from responsibility by avoiding real emotion and real reflection. The sentimentalist has no solution other than “love” and “empathy” (false ones).

To narrow it down, I’ll start with one of the most obvious examples of how sentimentality has gained a foothold in our age.

Lady Di – “England’s Rose”

When the divorced and scandal-ridden Lady Di died in a car crash in Paris on 31 August 1997, there was mass hysteria and a sentimental reaction – particularly in the UK, of course – but the whole of the Western world experienced similar tendencies.

The same tabloids that had stalked, harassed and tormented this modern-day Cinderella right up to the moment of her death turned 180 degrees and started glorifying the young corpse just before she was pronounced dead.

Tony Blair exploited the situation for his own gain, playing his cards just right (albeit totally without morals). The worst moment for me was when Elton John broke into his own classic “Candle in the Wind” during the funeral, with lyrics so obviously muddled that you could be sickened by anything less. Lady Di is “England’s Rose” – not only that, she’s actually the “soul” of the nation. I choose to quote the verse in full:

Goodbye England’s rose

From a country lost without your soul

Who’ll miss the wings of your compassion

More than you’ll ever know

The last line goes without saying, since the main character is actually dead. By the way: In the spirit of sentimentality, all proceeds from the sale of the single (the second biggest seller ever after “White Christmas”) went to charity, of course. That’s how you become “Sir Elton John” (1998).

Sentimentality in the shadow of terror

A series of terrorist attacks have hit Europe in recent years. The way the media, politicians, academia – and unfortunately also the people – have reacted to these atrocities is unfortunately strongly characterised by the same sentimentality. I will give some examples:

Our own experience of 22 July is typical. I think all Norwegians (over a certain age) remember the shock of 22 July, and we probably reacted in different ways – but most of us with grief and despair.

Here I feel the need to be quite clear: I’m not talking here about the reactions of those who were directly or indirectly affected by the terror, e.g. relatives, all members of AUF, all survivors of Utøya, even all members of the Labour Party. I personally have never experienced grief, and have no opinion on what reactions are natural.

But the public reaction (political, mass media, cultural elite) was strongly characterised by sentimentality.

In fact, we took sentimentality to such heights that we became a role model for an entire world: Look at Norway! They’re marching in praise and talking about “more democracy, more openness” (without following it up in practice, on the contrary).

The quote “If one man can show so much hate, think how much love we can all show together” spread around the world. Then there were more and more praise marches and other celebrations. After a while, I felt disgusted by it all. Especially since people were quick to look for scapegoats with the “wrong opinions”, e.g. Fjordman, document.no, anyone who voted FrP or anyone who didn’t love the multicultural project.

Moreover, the quote about the collective power of love is ideologically questionable. For one thing, it presupposes a collective that no longer exists, for which the insults from the left have been a little too loose over the past forty years (and vice versa, it must be admitted).

By the way: You can’t meet hate with “love”. As Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel said: The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference. By my definition, sentimentality is indifference.

Bruce Bawer has written a book (“The New Quislings – How the International Left Used the Oslo Massacre to Silence Debate About Islam”) about how the terror was subsequently used politically, which is well worth reading. For example, I actually believe that Stoltenberg meant it when he expressed his desire for “more democracy, more openness”. But unfortunately, many in the media and elsewhere on the left interpreted this to mean that “more democracy” meant stopping all criticism of Islam and the multicultural project.

Je suis Charlie

After the Charlie Hebdo massacre, we saw a new sentimental phenomenon: “Je suis Charlie” was suddenly appearing on millions of Facebook updates. The sentimentality had “gone viral”, as the saying goes.

But no-one was actually Charlie. Virtually no newspapers printed the images that were the background to the terror. Most uncomfortable was the march up the Champs-Élysées where (the responsible) world leaders marched in mourning, hand in hand, with Mahmoud Abbas in the centre of the line. Some carried placards of a broken pencil. None carried placards of what the issue was really about.

New expressions of sentimentality followed. Famous landmarks were lit up with the colours of the flag of the last affected country. New “hashtags” were constantly being created that could be used at the touch of a button. Teddy bears, candles and roses found new market segments. A German pianist with no particular musical abilities specialised in dragging around a piano in the aftermath of the terror to play “Imagine”. He even turned up at Jo Cox’s funeral. “It was very emotional,” said the Daily Mail.

After Bataclan, we saw the intolerance of sentimentality. When Jesse Hughes, lead singer of the rock band Eagles of Death Metal, refused to take the official, sentimental stance on the terror – but on the contrary pointed out that he suspected the whole thing was an “inside job” – that some of the security personnel (Muslim) must have opened the doors for the terrorists – and when he was also a Christian, a Republican and a supporter of the 2nd amendment – he was suddenly unwelcome at the memorial service for the tragedy a year later.

But the worst part for me was Manchester. That an entire stadium – just a few days after 22 mostly young girls were blown to bits (and over 100 injured), and many not even buried – can bring itself to sing “Don’t look back in anger”, well, it makes me wonder what Nietzsche would have said about such a thing.

When is it okay to be angry? Obviously not when you kill our kids. We already know (Rotherham, Telford) that rape on an almost industrial scale has to be accepted – you don’t want to spoil the good, multicultural atmosphere.

This was repeated in Southport. Hundreds of Brits are in jail for disapproving of the murder of little girls.

A final example: Alan Kurdi was three years old when he was found drowned after the rubber boat that was supposed to take him and his family to Europe sank. The images of the little boy on the beach created an immediate sentimental reaction and led to Europe opening its borders.

Few are numb to the images of the innocent boy. He can’t help it that his father risked his life for his own desire for better teeth (and possibly a life on benefits). But that doesn’t mean you should make politics out of that feeling.

The consequences of this sentimental attitude were disastrous: The number of deaths resulting from Europe’s reaction – especially Merkel’s open invitation – is something to be counted in the thousands. Kurdi doesn’t stay alive because thousands of others drown in the Mediterranean. And why is it that we always get to see close-ups of the dead children when they are from “somewhere else” – while no one shows pictures of the tortured victims after Bataclan, or the mutilated body of 11-year-old Ebba Åkerlund after the terror in Stockholm?

A picture of an illuminated Eiffel Tower was enough to be accepted as one of the good ones. Ten years later, the colours are Ukrainian.

Photo: AP /Christophe Ena/ NTB

Because sentimentality doesn’t tolerate proximity and reality. That becomes too difficult to relate to. The sentimentalists reduce Alan Kurdi to a Disney character who gives us a few “good tears”, often shared on Facebook.

You see something of the same thing in criminology: We are supposed to sympathise with the criminal. He is the victim of a “difficult childhood”, “socio-economic conditions” etc. Relating to the victim is too emotionally demanding. Then we have to deal with real pain and suffering (and who wants that?).

In politics, we find sentimentality en masse. I’ll give a few examples, but could of course go on for hours:

Aid

The whole concept of bilateral aid is based on a sentimental mindset. When Hareide, with mournful puppy-dog eyes, demanded more and more “aid” for “the poor” – that’s not true compassion, or a moral act, or an ethical choice. There is no morality in taking money from someone (us taxpayers), and then handing it out to others – like Mugabe, Palestinian terrorists, corrupt Brazilians etc.

But sentimentality makes it impossible to protest. If Hareide gives ten per cent of his own income to a cause he deems worthy, then I can respect him for that, regardless of whether I agree with the cause or not. But when he (and the rest of the Storting) takes almost 45,000 annually from my family and distributes it to causes I would almost without exception not support myself, it is an abuse in the age of sentimentality.

“Dreamers”

A few years ago, the US media talked incessantly about the so-called Dreamers. In other words: When you come up with the sentimental term “Dreamers” for illegal immigrants (who arrived in the US before the age of 18), the debate becomes impossible. Who’s against dreamers, anyway? Nobody talks about “Dreamers” when it comes to the poor Americans who have been a significant part of the population for generations.

You really get the feeling of living in a time where “die letzten Menschen” dominate. In fact, the demographic trend is such that if we’re not “the last people”, we’re certainly “the last Europeans”. We don’t even bother to procreate. We have no will to defend ourselves. We have no pride in anything – our oil wealth is “luck”, not the result of insane engineering feats and enormous efforts by divers and other oil workers.

Our national culture (if it exists at all) has no value. Our children have no hope of a better life than us parents. It is a betrayal without equal, and I feel guilty, even if I have not directly contributed to the development. Maybe I could have done more for my children? Well – at least I’m trying now. If there are enough of us, it will be harder to freeze us out. Democracy can be recreated if enough people care.

Is it possible to choose Nietzsche’s “yes to life” as “Übermensch” in our time? Well – I can suggest that we start by opting out of sentimentality. We have to accept that the world is the way it is before we can hope to change it. We need to stop labelling catastrophic trends in societal development as “challenges”.

We are “in deep shit”, but to give up hope is to give up the possibility of solutions. The solution can be bloody, violent, revolutionary, even peaceful and political – but also absent. But I personally have chosen a side, and my choice is to stand up for freedom of expression, individual rights and human life as an end, not as a means to some false utopia.

We must dare to face the truth in order to be able to find the right solutions. The future of our children is at stake.

As Nietzsche arrogantly says in his book “Ecce Homo”: “…to err is cowardice”.